Ayaan Hirsi Ali's crisis of faith

'Infidel' author, former atheist wrestles with meaning and purpose; chooses Christianity

The only position that leaves me with no cognitive dissonance is atheism. It is not a creed. Death is certain, replacing both the siren-song of Paradise and the dread of Hell. Life on this earth, with all its mystery and beauty and pain, is then to be lived far more intensely: we stumble and get up, we are sad, confident, insecure, feel loneliness and joy and love. There is nothing more; but I want nothing more. — Ayaan Hirsi Ali, “Infidel” (2007)

These beautiful and poignant thoughts were penned by Ayaan Hirsi Ali some 16 years ago, but they wouldn’t be her final word on such grave matters, for she has more or less abandoned the entirety of it and turned — returned — to what she described as the “spiritual solace” of faith.

Ali, author of the 2007 work, “Infidel,” in which she recounts the harrowing story of her flight from Kenya to escape a forced Islamic marriage and seek political asylum in the Netherlands to atheism, announced in a piece on UnHerd.com that she was now a Christian.

Once considered one of the New Atheists alongside authors and thinkers like Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett, Ali became a staunch critic of Islam and a defender of women’s rights in Muslim-majority countries after growing up on a fundamentalist reading of Islamic scripture in Kenya, where she lived “by the book, for the book,” as she described it during a speech at the Sydney Writers’ Festival in 2007. She became a disciple of the Muslim Brotherhood, started wearing a burka and eschewed everything associated with Western culture. She was told to disassociate herself from unbelievers and, most of all, to hate the Jews.

A ‘zero-sum escape’

She said in the UnHerd essay that when she found atheism after moving to the Netherlands, it had a kind of freeing effect, and when she read Bertrand Russell’s 1927 lecture, “Why I Am Not a Christian,” it offered a

zero-cost escape from an unbearable life of self-denial and harassment of other people. For him, there was no credible case for the existence of God. Religion, Russell argued, was rooted in fear: “Fear is the basis of the whole thing — fear of the mysterious, fear of defeat, fear of death.”

This is a curious reason to become an atheist.

In her essay, we don’t find a renunciation of Islam on theological grounds or epistemological grounds. We don’t find a rigorous critique of the Quran itself or of the half-baked tale about Muhammad meeting the angel Gabriel in a cave, where the angel commanded the illiterate man to “Read!” several times and then finally revealed scripture to him. We don’t find a summary of other religions that Ali had studied and why they weren’t considered instead of Islam. If Ali found Islam too repugnant and off-putting, why not some other, more tolerant religion or faith at this time in her spiritual journey. Indeed, fear of death and the unknown is the very reason many people turn to faith, not run away from it. So why jump right to atheism?

Perhaps Ali was persuaded by Russell’s logic about the existence of god, but if so, she doesn’t say so here, except to note that, for Russell, “there was no credible case” for a god.” She just tells us that a release from fear was the main basis for her deconversion, and as she adds, almost parenthetically, that atheists like Hitchens and Dawkins were “clever” and a “great deal of fun.”

So too, like her deconversion from Islam to atheism, her decision to accept Christianity in this essay brings up more questions than answers and offers no points on theology, the truth of the Bible, the life of Jesus, why she thinks he is a deity worthy of worship or why she thinks he existed at all. In fact, she mentions scant little about Jesus, only to say that “Christ’s teaching implied not only a circumscribed role for religion as something separate from politics. It also implied compassion for the sinner and humility for the believer.”

For a person like Ali who found Russell’s crisp logic so attractive that it inspired her to give up her childhood faith, one might have expected at least a point or two about why she thought Christianity could withstand the doubt and skepticism of a thinking person like herself, one who doesn’t just take ancient scripture at face value. But there is none of that here. Granted, her essay was not meant to be a rigorous defense of Christianity, but for a person to make such a leap from outright atheism to belief in a deity who died and rose from the dead, breaking the laws of physics all the while, a word or two about how someone squares this logic in their heads or why she finds the Bible convincing as a path to truth might have been fitting.

The four evils

In any case, based on this essay, her newfound belief in Christ boils down to two points, neither of which have much at all to do with Jesus.

First, she thinks that belief in Christianity and Judeo-Christian values and traditions is central to tackling what she views as our most pressing concerns: China, Russia, Islamism and “the viral spread of woke ideology.” I’m not sure how “woke ideology” is on par with threats from regimes that could unmake our world if left unchecked, but this is, nonetheless, among her top concerns globally. I should note here that shoehorning wokeness into her list of dooms probably has a lot to do with her turn, some two decades ago, from a left of center political outlook to a right of center one, the latter of which seemed to have ramped up after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on American soil by 19 Islamic terrorists.

In her estimation, we should meet today’s challenges by answering the question, “what is it that unites us?”

The only credible answer, I believe, lies in our (our?) desire to uphold the legacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition. … That legacy consists of an elaborate set of ideas and institutions designed to safeguard human life, freedom and dignity — from the nation state and the rule of law to the institutions of science, health and learning.

For Ali, atheists like Russell and Hitchens were too narrowly focused on the existence of god and the ills of religion when they should have considered the significant freedoms that a Judeo-Christian framework have afforded the West — the freedom, for instance, that Russell enjoyed when he delivered his “Why I Am Not a Christian” speech to (“former or at least doubting) Christians in a Christian country” in London. She invites us to imagine a Muslim delivering a similar message in a Muslim nation. The question she implies, but never quite gets around to asking directly is, “would such a speech be allowed in a Muslim-majority nation or would that person be run out of town, at best, or at worst, maimed or executed for their exceedingly unpopular and heretical beliefs?”

Of course, not all Muslim-majority nations take a hard line on freedom of speech based on religion, and the reality globally is much more complicated than what the above scenario indicates.

Freedom then and now

As a study by the International Journal of Communication points out, more than 95 percent of Muslim-majority nations have freedom of speech protections and more than 87 percent protect freedom of the press in their founding documents, even though actual freedom on the ground varies greatly between countries.

In sum, even though the inclusion of religion and religious laws in the constitution can be a factor in the restriction of freedom of speech and press, the actual freedom in a country likely depends more on the political regime and the history or culture of the country, rather than recognition of Islam as a state religion alone.

The point here is that the secular makeup or culture of the nation itself, rather than solely religion, usually determines how much actual freedom citizens have in practice. Tunisia names Islam as the state religion in its constitution, but is one of the most free Muslim-majority nations in the region, according to the study. Conversely, Turkey, a largely secular state, has imposed penalties for speaking against the government. According to the study:

The inclusion of freedom of speech and press in the constitutions is the building block of such freedom in societies, but it is reliant on the culture and the political regimes in power.

The other point is that generalizing about how all Muslim audiences would react to a speech on why a person was not a Muslim is problematic conjecture. But an analysis of radical or liberal ideologies among Muslim-majority nations is a large topic of discussion and is well beyond the scope of this piece. Suffice it to say that, however unfree certain areas of the Middle East might still be with regard to free speech and freedom of the press, it’s not like many traditional Western nations have a good track record on personal liberties either when one considers how long many of them have been in existence and how decidedly unfree they were for centuries. So, even though Islam is certainly deserving of criticism for its record on free speech and expression, the West can hardly claim the moral high ground.

Ali goes on to say that “freedom of conscience and speech is perhaps the greatest benefit of Western civilisation.”

It does not come naturally to man. It is the product of centuries of debate within Jewish and Christian communities. It was these debates that advanced science and reason, diminished cruelty, suppressed superstitions, and built institutions to order and protect life, while guaranteeing freedom to as many people as possible.

Again, her point is an odd one to make when these same Christian communities are guilty of generations and centuries of oppression, slavery and barbarism against people whose main crime was not believing in the same god, in addition to the other crime, of course, in the case of slavery: not being white. Her argument is odder still when one considers that the Judeo-Christian communities existing prior to debates that eventually led to more enlightened thinking — you know, sans all the slavery and oppression — were vastly more religious than their modern counterparts, which have become increasingly secular and less reliant on faith.

Rising shares of adults in Western Europe describe themselves as religiously unaffiliated, and about half or more in several countries say they are neither religious nor spiritual.

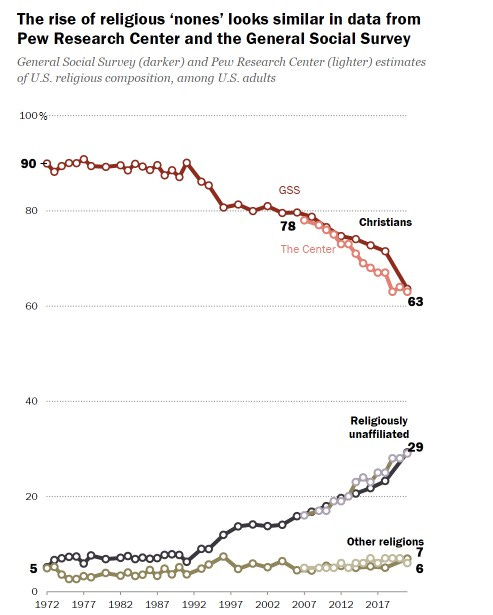

The same is true, in fact, in the United States:

And again, in Europe, the trend toward more, not less, secularism among young people is stark:

Secularization trends aside, the fact that Christian-majority nations only somewhat recently came on board with human rights and personal liberty protections, while many Muslim-majority nations are still struggling to climb out of the Dark Ages, is cold comfort. Both religions are complicit in disturbing levels of human misery and oppression, and if they both believe in and serve immutable gods — as they most certainly claim to do — that begs the question: why did it take centuries for them to build, or work toward, a more empathetic, understanding and permissive society?

The “legacy of the Judeo-Christian society” that Ali so glowingly writes about in this piece is pockmarked with moral, ethical and logical inconsistencies, and if it is now so self-evidently working to “safeguard human life, freedom and dignity,” why wasn’t it always working to do so? The last several decades is a little late in the game to be making claims about the moral virtues of Judeo-Christian when centuries of abuse and oppression of human beings by Christians paints an uglier picture.

Meaning and Purpose

The other main reason Ali gave for turning to Christianity was that she

ultimately found life without any spiritual solace unendurable (emphasis mine) — indeed very nearly self-destructive. Atheism failed to answer a simple question: what is the meaning and purpose of life?

Interestingly, and perhaps tellingly, Ali previously described life as a Muslim as being an “unbearable life of self-denial and harassment of other people,” and then she came to find life as an atheist to be “unendurable,” as she writes above. One wonders how life as a Christian will go.

Religion alone doesn’t provide a purpose and meaning in life. Do Christians stare at the wall all day and proclaim, “I have found purpose and meaning in life because of my relationship with Jesus, and so there is nothing else for me to do?” No. They lead lives pretty similar to atheists and people of other faiths, they may be surprised to learn. One will find that, no matter how much believers claim that their faith gives them purpose and meaning, they still take jobs to feel personally or intellectually fulfilled; they still have families to feel loved and part of something larger than themselves; they still appreciate and pursue art or literature or music to fill them up emotionally. They pursue all of these things that provide purpose, meaning and fulfillment.

Atheism’s job is not to provide a reason for living. Atheism has no job, purpose or underlying ideology attached to it at all; it is simply the disbelief in a god or gods. Life is what we make it, and while Christians might augment their emotional or spiritual experience with church services, scripture and praying, they still carry on pretty much like everyone else.

There is, of course, a kind of “spiritual solace” to be had without religion. One can revel in the beauty and glory of nature. A person can look up at the cosmos and proclaim, as Neil deGrasse Tyson does, that we are literally stardust and are inseparable from the universe. One can get in touch with the present moment, as the Zen Buddhists do, and recognize how valuable — invaluable — each moment of existence on Earth truly is. Read an inspiring book. Paint a landscape. Learn an instrument. Drive to the sea and sit in awe.

Ironically, the self-proclaimed anti-theist and one of the most staunch enemies of religion in our lifetime, Hitchens, penned the preface to Ali’s book, “Infidel,” and said at the time in 2007 that she was “much wiser than many thousands of academics and pundits” for working out for herself via the “crucible of personal experience” the many dangerous ideologies that religion, and particularly fundamentalist Islam, had unleashed on mankind.

Hitchens, who died in 2011, was the kind of person who never went searching for meaning. He was an extraordinary reveler in life and found his intellectual, and dare I say, spiritual, fulfillment in art and literature and debate and song. To take a line from Thomas Wolfe’s monumental coming of age novel, “O Lost:”

He loved the world and all the hum and clacking noise of life.

Perhaps if Ali had read one of Hitchens’ last works, “Hitch-22: A Memoir,” she could have renewed her passion for secularism and an unflinching life firmly grounded in reality that she so eloquently described in “Infidel,” for Hitchens already provided his answer to the meaning of life question:

A life that partakes even a little of friendship, love, irony, humor, parenthood, literature, and music, and the chance to take part in battles for the liberation of others cannot be called ‘meaningless’ except if the person living it is also an existentialist and elects to call it so. It could be that all existence is a pointless joke, but it is not in fact possible to live one’s everyday life as if this were so. Whereas if one sought to define meaninglessness and futility, the idea that a human life should be expended in the guilty, fearful, self-obsessed propitiation of supernatural nonentities… but there, there. Enough.

One wonders what the great polemicist, who once found so much promise in Ali’s courage and conviction after reading her book, would have to say now.